A Calendar Puzzle and Dancing Links

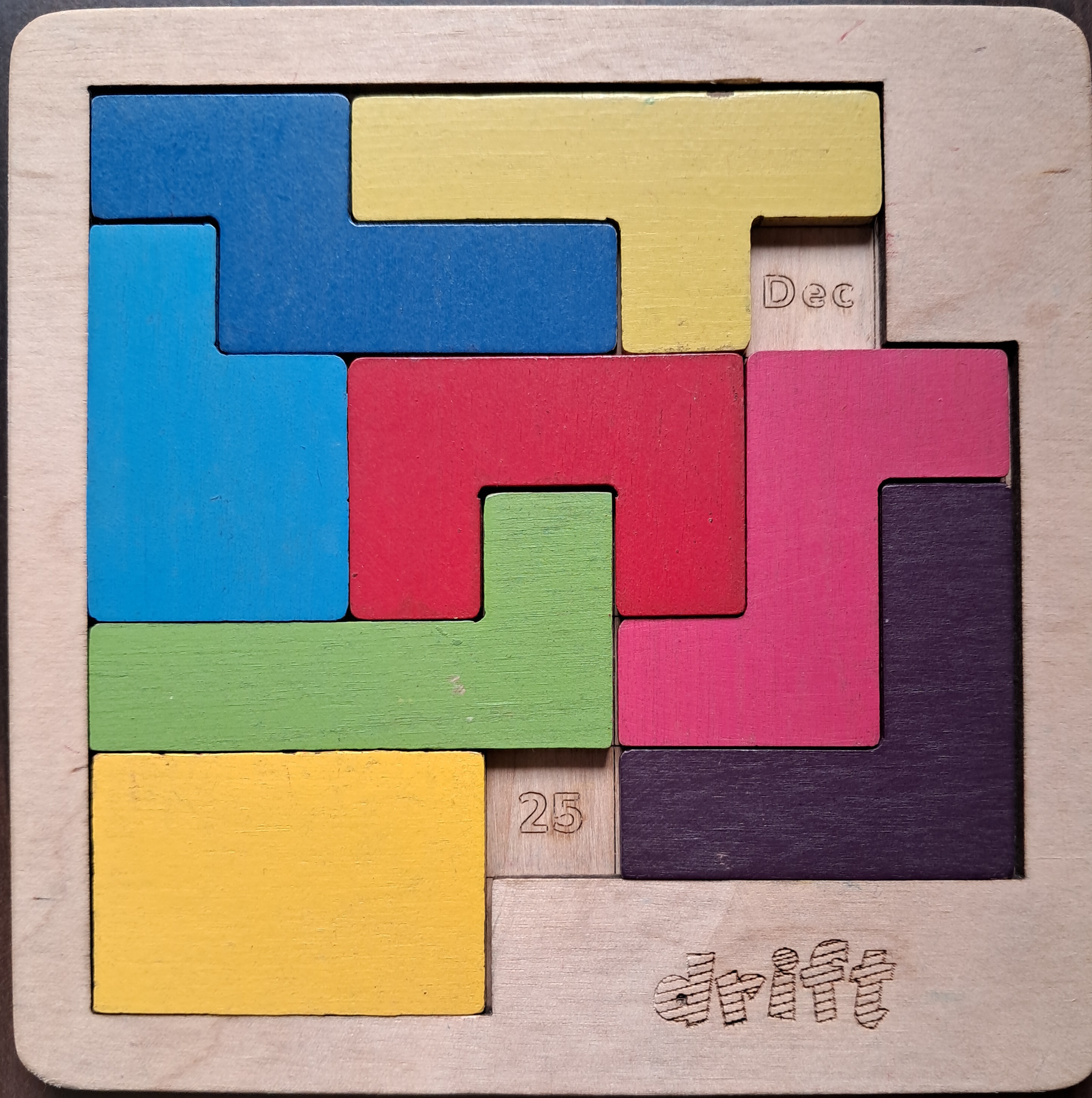

A few months back we were gifted an interesting puzzle by a friend.

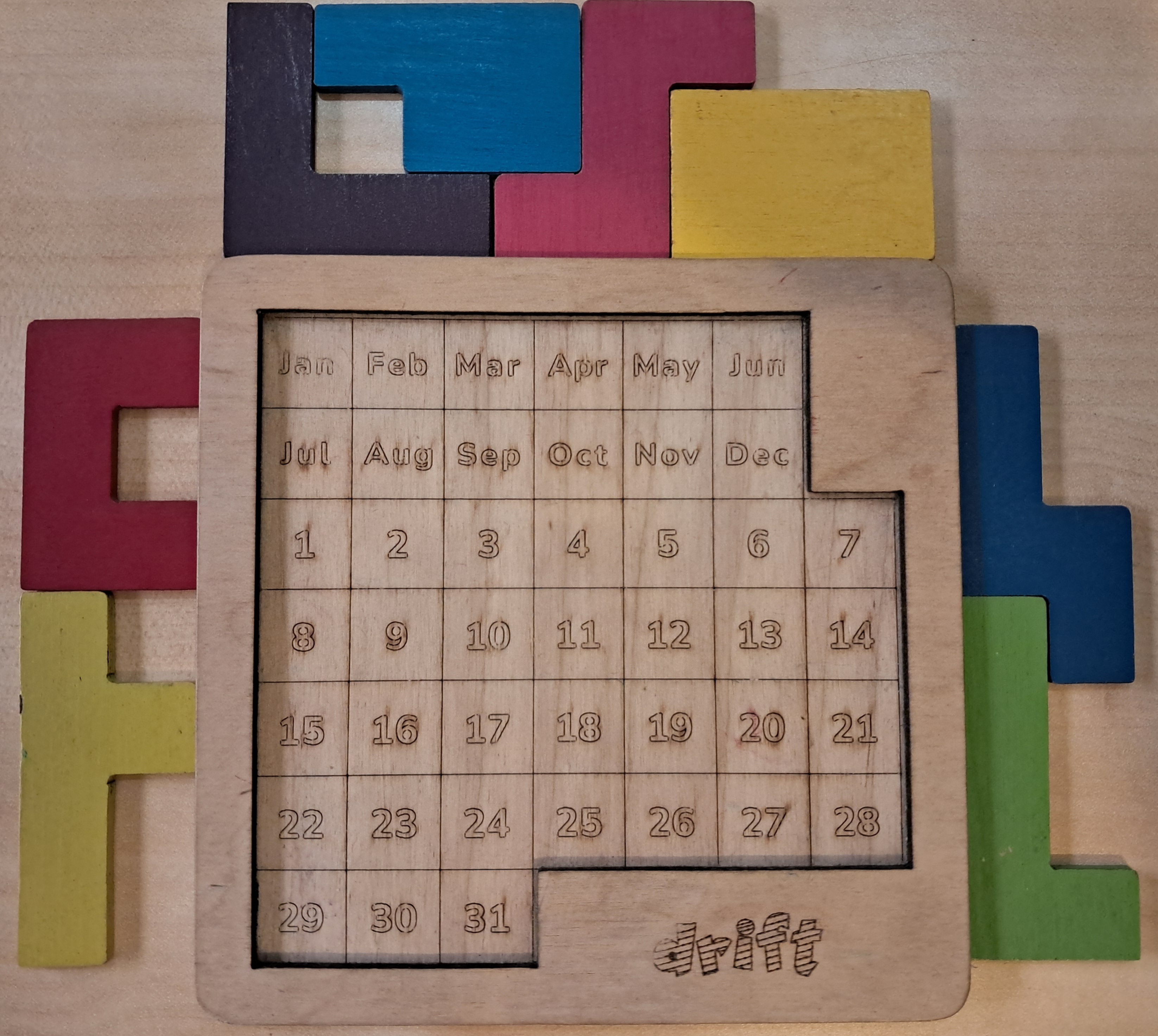

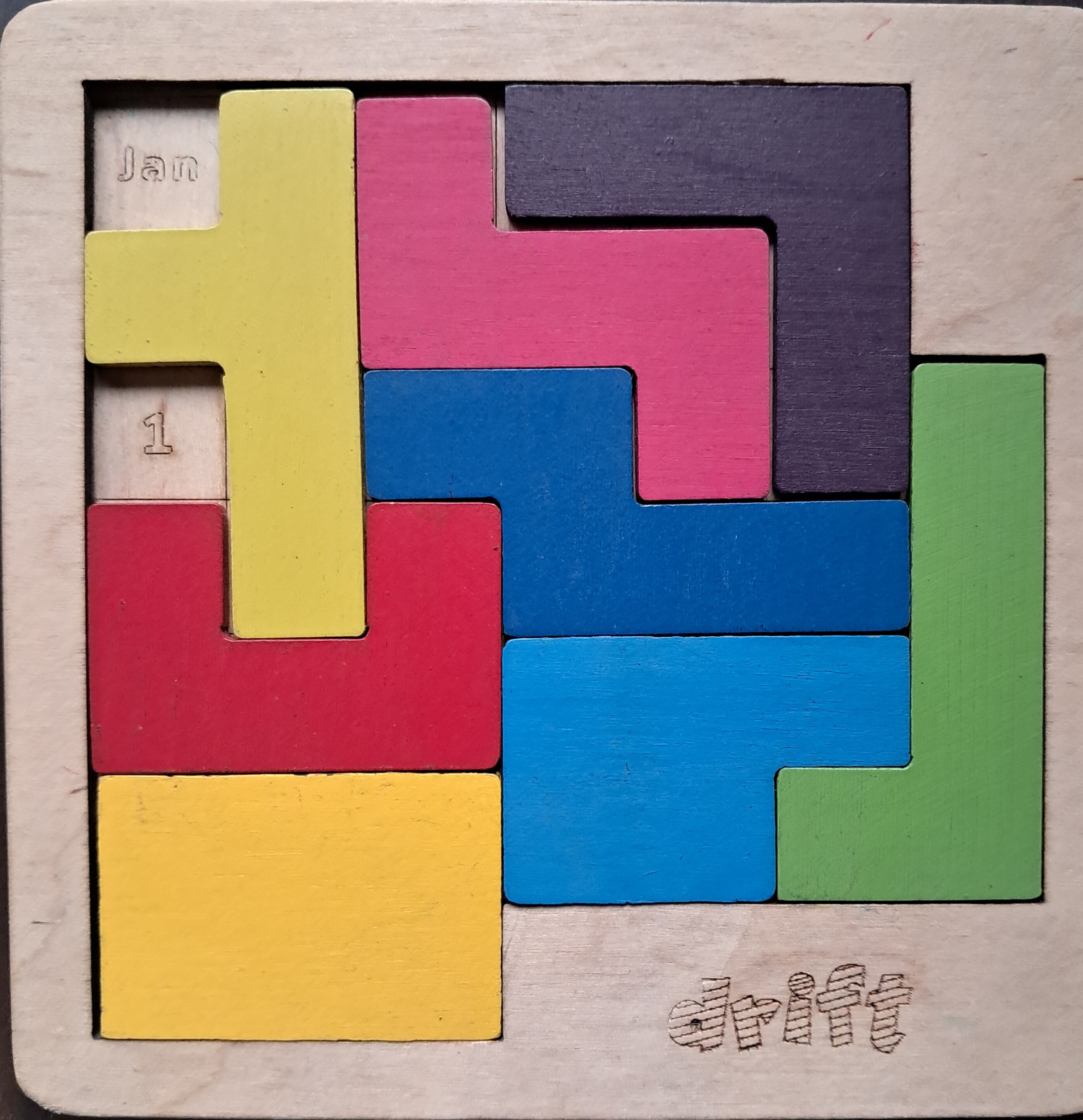

Available for sale here, the puzzle consists of a grid of squares marked with the 12 months and 31 days of the calendar. The goal is to place the 8 jigsaw pieces so they cover all squares except the current date. Seven of the pieces are in the shape of a pentomino covering five squares each, while the eighth is a solid block of six squares. You are allowed to rotate and flip the pieces as you wish.

The beauty of this simple construction is that every day brings a fresh new puzzle. You cannot simply adjust a couple of pieces to go from one date to the next. Indeed, it is not obvious that the puzzle can even be solved for each day of the year.

Having played with it for a few days, I decided to try and write a solver that could generate the configurations(s) for a particular date. The rest of this post describes how I went about it; the final code is available in this repository as a Python notebok.

I first thought of mimicking the human approach of trial and error. Add pieces one by one till you reach a dead-end, then backtrack by removing a couple of pieces and try again. In Python(ish) pseudocode:

def solve(board, target, working_solution=[]):

#If target is reached, print solution

if board == target:

print("Success!", current_solution)

remaining_pieces = get_remaining(board)

for piece in remaining_pieces:

for orientation in get_orientations(piece):

for position in get_valid_positions(board, orientation):

# Make a move by placing a remaining piece on the board

move = (piece, orientation, position)

new_board = make_move(board, move)

# Recurse with updated board and working_solution

solve(new_board, target, working_solution + [move])This is not wrong as it stands but a few devils lurk in the details. Getting the remaining pieces is simple enough, but what about get_valid_positions? Once we choose a move i.e. place a piece on the grid, some moves that were valid earlier are eliminated because the next piece cannot overlap with the current one. However several other moves might still remain valid. Instead of exploiting this pattern, we repeat bits of the same work over and over again. One wonders if such a program would terminate in a reasonable time.

As it happens, I had just come across Donald Knuth’s Christmas lecture and paper on his Dancing Links algorithm. He shows that many puzzles with rigid overlapping constraints can framed as exact cover problems. Sudoku and Eight Queens also belong to the same family.

Knuth’s paper has two parts:

- A reformulation of the question into a matrix that treats the possibilities and constraints on an equal footing. He calls this Algorithm X.

- A representation of this sparse matrix in terms of doubly linked lists which makes it easy to solve recursively.

For our solver we will use the first part. Instead of linked lists which are overkill for this problem, regular arrays will suffice to implement Algorithm X. We do have to be careful in avoiding dead-ends and not repeating solutions (more on this later).

Matrix M and Algorithm X

In this section we will see how all the data and constraints in our puzzle can be distilled into a single matrix.

Consider what happens when make a move and place a piece on the grid:

- The piece cannot be reused.

- The squares that it covers, cannot be touched again.

Correspondingly, in our matrix M:

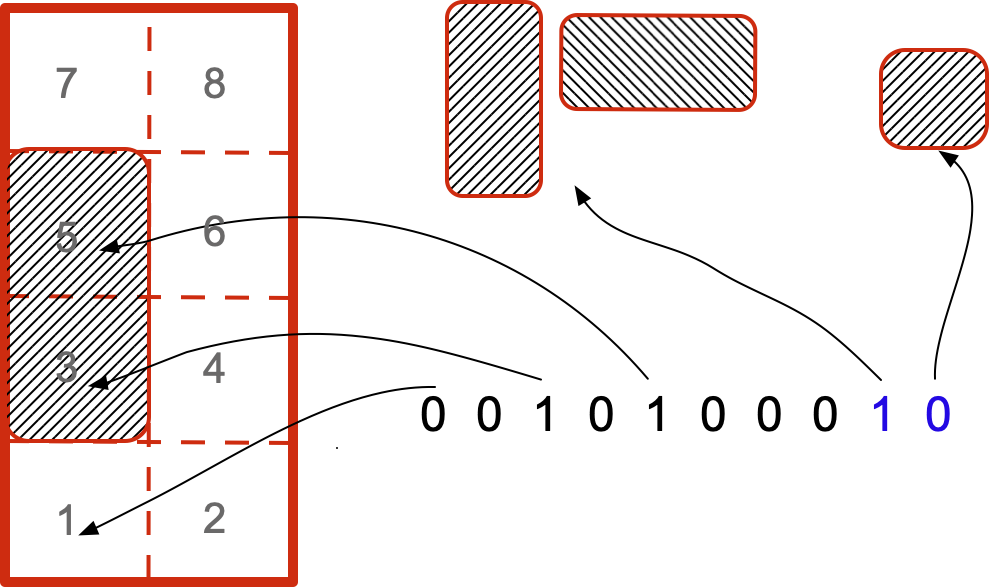

- Each row represents one way to place a piece on the board.

- Each column represents either a square that needs to be covered or a piece that we can use.

- A 1 in the matrix means “this move covers this square” or “this move uses this piece”. Why combine these two notions? Since both are possibilities that have been eliminated by the move, we use columns keep track of them together. This is Knuth’s remarkable insight.

To understand how this works, let us look at a simple example.

We recast the solution. Recall that move is a row, call it r.

- Mark each column that intersects r i.e. where r has a 1. Call this set C.

- Mark each row that intersects C i.e. has a 1 in any of those columns. Call this set R.

What do C and R mean in terms of the puzzle?

Making a move covers certain squares and uses up a piece. Those are exactly the columns in C.

Making a move also blocks certain other moves forever viz. those that overlap the same squares or use the same piece. These are the rows in R.

I hope it is now clear that making a move eliminates the rows R and columns C from the matrix. The shortened matrix automatically contains the remaining legal moves and no others. So we can make another move and so on till:

Dead-end There is at least one remaining column that intersects none of the remaining rows. In other words, there is a square that can never be covered or a remaining piece that cannot be placed legally.

Success No columns remain. All target squares have been covered and we have reached a solution.

We have arrived at Algorithm X. Here is the pseudocode of a version that prints solutions as they are found.

solve(M, moves)

if no columns in M:

print("Success", moves)

return True

elif no rows intersecting columns:

return None #Dead-end. No point going further.

for r in rows:

new_moves = moves + [r]

C = [j for j in columns if M[i,j] == 1]

R = [i for i in rows if M[i,jj] == 1 for some jj in C]

new_M = remove_rows_and_columns(M, R, C)

solve(new_M, moves)

return NoneCoding it up

I will use Python and Numpy as those are what I know best. I present some of the code in snippets - the complete solution along with accompanying functions to plot solutions (very important for debugging!) can be found this (repository)[https://github.com/metterklume/calendar-algorithm-x].

Some Numpy idioms might be a bit opaque to the uninitiated. Ignore them at first reading as long as the purpose makes sense.

The Pieces

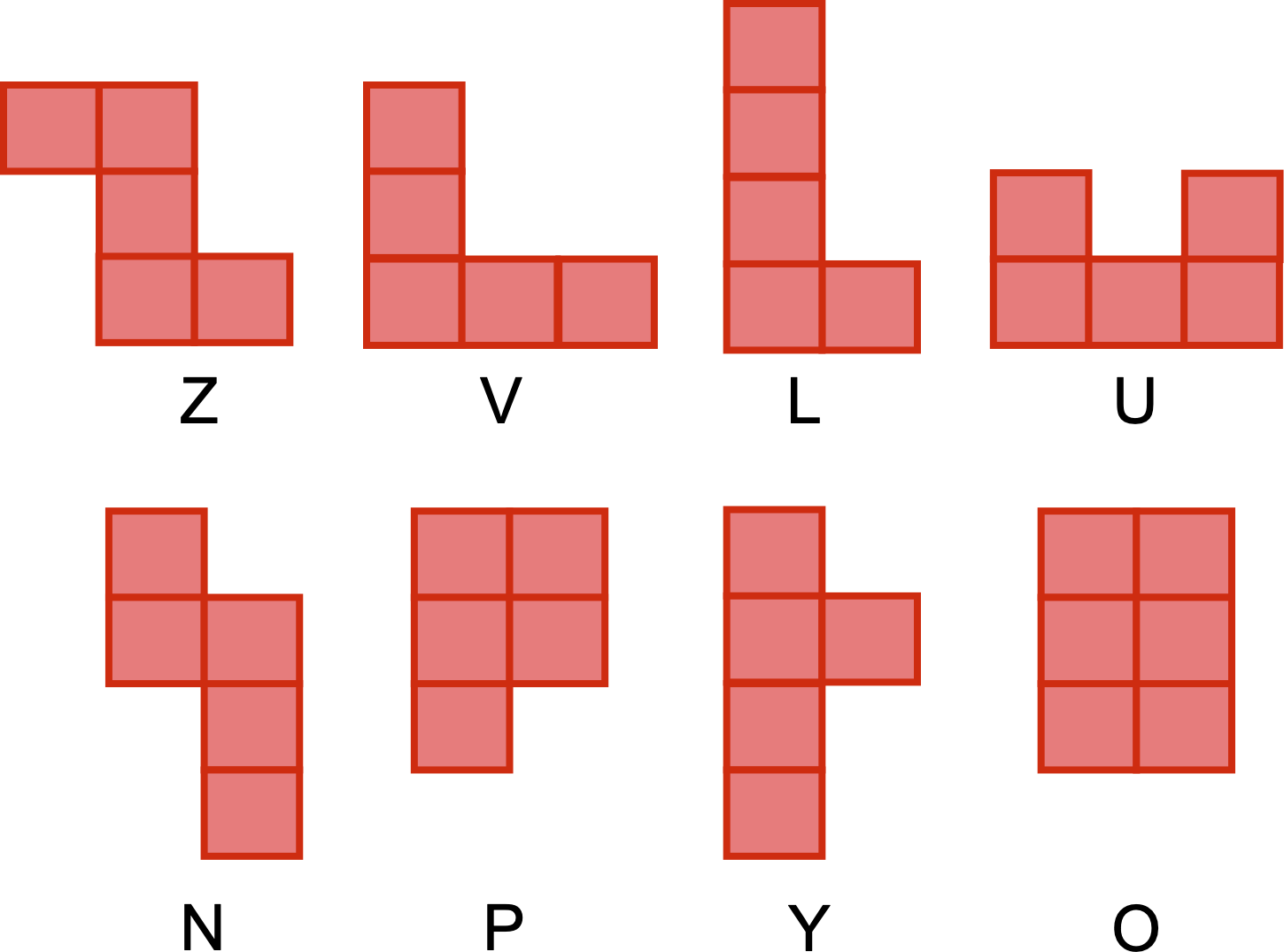

Following the conventions in wikipedia I am going to name the 5 square pentomino pieces by letters - N,V,Z,U,Y,P,L. The last one with six squares, we call O. The labels are just an aid for bookkeeping; they do not play a part in the solution.

We first find all variants of the pieces. A simple way to do this is to convert each of the eight pieces into an array.

Each piece as a "bitmapped" array

N = np.array([[1, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

V = np.array([[1, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

Z = np.array([[1, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

U = np.array([[1, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

Y = np.array([[0, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

P = np.array([[1, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 0]], dtype=np.int32)

L = np.array([[1, 0],

[1, 0],

[1, 0],

[1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

O = np.array([[1, 1],

[1, 1],

[1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)We are free to rotate the pieces by 90 degrees a la Tetris, and flip them over (unlike Tetris). Fortunately we do not have to write out each variant by hand.

Find all variants of the original 8

def crop(piece):

"""Crop the grid to the smallest rectangle containing all the 1's"""

allx, ally = np.where(piece)

return piece[min(allx):max(allx)+1, min(ally):max(ally)+1]

def apply_symmetry(piece):

"""Take a piece array and return a list of its unique 90 degree rotations and reflections"""

ways = []

for i in range(0,4):

R = crop(np.rot90(piece, i))

if not any(R.shape==x.shape and (R==x).all() for x in ways):

ways += [R]

piece = np.fliplr(piece)

for i in range(0,4):

R = crop(np.rot90(piece, i))

if not any(R.shape==x.shape and (R==x).all() for x in ways):

ways += [R]

return ways

pieces = (N,V,Z,U,Y,P,L,O)

allpieces, labels = [], []

##allpieces is a list of all unique pieces. the labels are the indices (0-7)of the original piece

for label,piece in enumerate(pieces):

ways = apply_symmetry(piece)

plot_grid(4,grid=piece)

print(len(ways))

allpieces += ways

labels += [label]*len(ways)

Create the initial grid as an array with a particular day and month blocked.

def create_initial_grid(month=None, day=None):

"""The initial grid as a 7x7 array with 1's showing squares that are blocked out.

6 squares are always blocked.

We add 2 squares with the given month (1-12) and day (1-31) marked as in the

photograph of the puzzle."""

initial_grid = np.array([[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1]], dtype=np.int32)

if month is not None:

i = (month-1) // 6

j = (month-1)%6

initial_grid[i,j]=1

if day is not None:

i = ((day-1) // 7) + 2

j = (day-1)%7

initial_grid[i,j]=1

return initial_gridCreate the rows by sliding each piece variant in the initial grid and checking valid positions.

brows, bcols = np.where(initial_grid)

blocked = set(i*7+j for (i,j) in zip(brows,bcols))

def make_rows(piece, blocked):

"""

Slide the piece in the 7x7 grid and return the rows that correspond to valid moves.

A valid move is one that does not overlap with any of the blocked squares.

Each row is a 49-bit array with 1's in the squares that are covered by the piece.

"""

x_max, y_max = piece.shape

allx, ally = np.where(piece)

rows = []

for i in range(7-x_max+1):

for j in range(7-y_max+1):

squares = [(i+x,j+y) for (x,y) in zip(allx,ally)]

if any(7*a+b in blocked for (a,b) in squares):

continue

squares = [7*a+b for (a,b) in squares]

row = np.zeros(49, dtype=np.int32)

row[squares] = 1

rows.append(row)

return rowsAdd a suffix to each row with the label of the corresponding piece.

M = []

for label, piece in zip(labels, allpieces):

rows = make_rows(piece, blocked)

suffix = [0]*8

suffix[label] = 1

rows = [np.hstack((row,suffix)) for row in rows]

M += rows

M = np.array(M, dtype=np.int32)

We have finally arrived at the master matrix M, a distillation of the original puzzle with exactly the data needed to solve it. All that remains is to find solution(s) by recursively making moves and deleting rows and columns as we saw earlier. But a couple of practical problems need to addressed.

Optimization

First, how are rows and columns to be removed? The most naive way would be to create a fresh matrix every time. Apart from efficiency issues, this also complicates how we keep track of the solution as the row indices refer to successive (smaller) matrices. The next simplest way is to leave the matrix unchanged but keep track of the rows and columns that remain. I do this by a boolean “bit-array” - the index is True if the row remains, False if it has been removed in a previous step.

Second, note that each unique solution will be reached in 7!=5040 ways, once for each permutation of the pieces. This would increase the running time by three orders of magnitude! I single out a unique permutation by only taking moves that cover the top-leftmost empty square. This is equivalent to restricting to those rows that intersect the first remaining column.

I believe these choices are in keeping with the master’s most famous dictum.

We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil.

The solver

def solve(M, keep_rows, keep_cols, working_solution):

"""

keep_rows[i] = True if the move in row i can be made, else False

keep_cols[j] = True if the square of column j is empty or the piece is available, else False

working_solution is the current list of moves (row indices)

n = 49 is the number of squares in the grid, hardcoded for now

"""

n = 49

#If all squares are covered, we have a solution

if not keep_cols[:n].any():

print( "success!", working_solution[1:])

return True

#If at least one square cannot be covered by a square,

#we have reached a dead-end.

elif not M[keep_rows].sum(axis=0)[:n][keep_cols[:n]].all():

return None

#Only take moves that cover the top-leftmost square that is currently empty

#<==> rows that intersect the first remaining column

#This automatically picks a unique permutation of the pieces

leftrows = np.where(M[:,np.where(keep_cols)[0][0]])[0]

for r in leftrows:

if not keep_rows[r]:

continue

new_keep_rows, new_keep_cols, new_solution = keep_rows.copy(), keep_cols.copy(), working_solution.copy()

new_keep_rows[r] = False

cols = np.where(M[r])[0]

for c in cols:

#remove all squares covered by the piece and the piece itself

new_keep_cols[c] = False

#remove all moves that overlap with the piece that we have just placed

for rr in np.where(M[:,c])[0]:

new_keep_rows[rr] = False

new_solution.append(r)

solve(M, new_keep_rows, new_keep_cols, new_solution)

return None

#A slight technicality. Initiall all rows are free. But we must remove the columns

#corresponding to the squares that are already blocked.

chop_cols = [i for (i,c) in enumerate(M.T) if not c.any()]

keep_cols = [c not in chop_cols for c in range(M.shape[1])]

keep_rows = [True]*M.shape[0]

Alright, let’s fire it up and solve for Christmas.

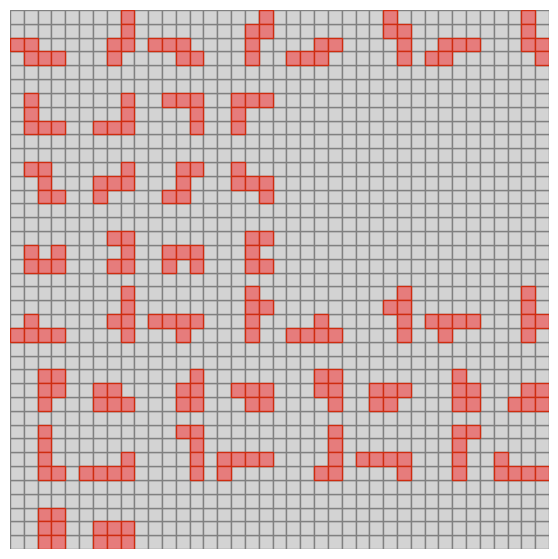

It turns out there are as many as 92 distinct solutions. Here are a few others.

Final Thoughts

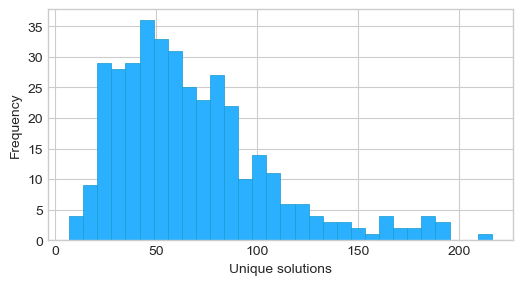

Fiddling with this puzzle with my morning tea, some dates were a bit easier to solve than others but none were totally trivial. On several days I gave up; on rarer occasions I would find two separate answers. This did make me wonder how many solutions there are for a typical date. A large number of solutions would mean the problem was easier for that date while a single solution would be harder to find.

Letting the solver churn for all 31x12 days gives a surprise. There are 67 solutions on average for each date! The record-holder is Jan 25 with 216 solutions. We can safely conclude that I am terrible at these puzzles.

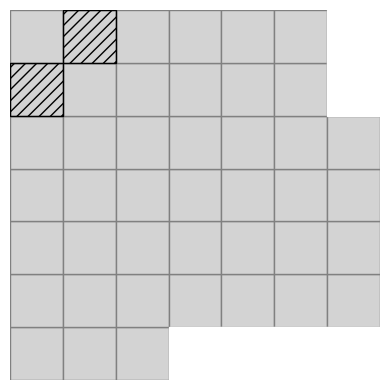

What if we relax the problem a bit from the month-day combinations, to configurations that leave any two given squares uncovered? It is easy to find combinations that are trivially unsolveable.

It seems that these are the only unsolveable problems. However there is one problem with a unique solution. Here it is: